You can listen to or watch this article here:

In my blog post “The Meaning of Blockchain Immutability” I explained immutability from the perspective of the beneficiaries, who are all people globally and their basic rights.

In that post I wrote:

This is why we need individual security to minimize the risks to our independence, local knowledge, and ability to conduct and implement our unique life plans.

For that we created basic rights such as property, freedom of contract, privacy, free speech, freedom of assembly, religion, and many more. Those basic rights are implicit, embedded, and distributed globally within blockchain networks.

Basic rights are represented on blockchains by means of ledgers with accounts, balances, assets, programs, and smart contracts, which cross all borders and reach everyone in the world regardless of their country, culture, ideology, beliefs, gender, race, or any other human condition.

Protecting those basic rights, sound blockchain principles, such as trust minimization, immutability, censorship resistance, and least authority, must exist as norms within public blockchains and their extended ecosystems to assure their integrity and continuity.

However, many people are still puzzled by the concept of immutability and what it entails specifically in blockchains such as Ethereum Classic (ETC). The reason for this is that networks as ETC have several parts, and some protect the basic rights described above directly, but others do it indirectly.

In this post I will describe the meaning of immutability in ETC, but with more focus on the operating network and protocol.

1. The Concept of Security

The first thing I think about when analyzing immutability is the concept of security. Blockchains are all about security. The problem is that security is really a negative, the absence of damage or cost, so it’s not tangible or something we see objectively, unless they happen.

Due to this, I describe security as “the absence of losses” or “the minimization of losses”.

A loss is not only financial, but may also be the loss of non-monetary things such as other kinds of resources (e.g. food, shelter, transport, etc.), indirect sources of income (e.g. the life of a breadwinner), in the case of blockchains, the loss of integrity of the system itself, which contains people’s guarantees and basic rights (e.g. property, agreements, free speech, etc.), or a more nuanced type of loss, especially in our modern world, which may be the correct and reliable operation of systems (e.g. decentralized software programs, decentralized application – or dapp – functionality, device functionality, etc.).

2. Hazards, Risks, Perils, and Losses

To analyze what conditions create the potential losses described above, it is useful to deconstruct the cause and effect chain of components that lead to them.

Hazards:

Hazards are the things that increase the probability that a loss due to a specific peril may occur. In the case of lung cancer (the peril), smoking is a hazard that increases the probability of a person getting cancer, thus dying (the loss). In the case of a home, having low quality pipes is a hazard that may increase the probability of internal flooding (the peril) that may damage the floor and furniture (the loss). In the case of property and agreements on a blockchain, making rushed changes without proper testing is a hazard that may increase the probability of future failures or hacks (the perils) that may breach property and agreements (the losses).

Risks:

As described above, risks are the mathematical probabilities of perils happening that may cause losses. It is important for blockchain ecosystems to be aware and have proper risk management, threat models, assumptions and, whenever possible, quantification of what these risks are so that the hazards that increase them may be better identified and minimized.

For example, if blockchains primarily provide security by means of minimizing trusted third parties, then the main risk they have is trusted third parties taking over. This means that any feature or rule change that increases the influence of any person, constituent, or institution is a hazard that increases the risk of perils that may lead to losses on the blockchain.

Perils:

Perils are the concrete actions or things that directly cause losses. As described in section 3 below, blockchains have two parts that may be manipulated or modified that may cause losses directly or indirectly: The state of the network and the rules of the network.

It is important to identify and separate both parts to clarify further what immutability means from the different perspectives.

Losses:

As described above, losses are the concrete decrease of wealth, financial wellbeing, savings, or money, but also non-financial things, such as the integrity of basic rights, property, agreements, or the loss of functionality of systems such as dapps, devices, robots, and other things that may be built on top of blockchains such as Ethereum Classic.

Blockchains may also be the base platforms of social systems such as democracies, voting mechanisms, distributive schemes, corporations, other legal persons, or other types of coordinating devices.

The concept of loss may expand significantly in the future as networks as Ethereum Classic evolve and become more central to people, businesses, and systems around the world.

3. Model: State vs Rules Immutability

In a recent interview Anthony Lusardy, US Director of the Ethereum Classic Cooperative, said “when I say immutability…I mean immutability of state”.

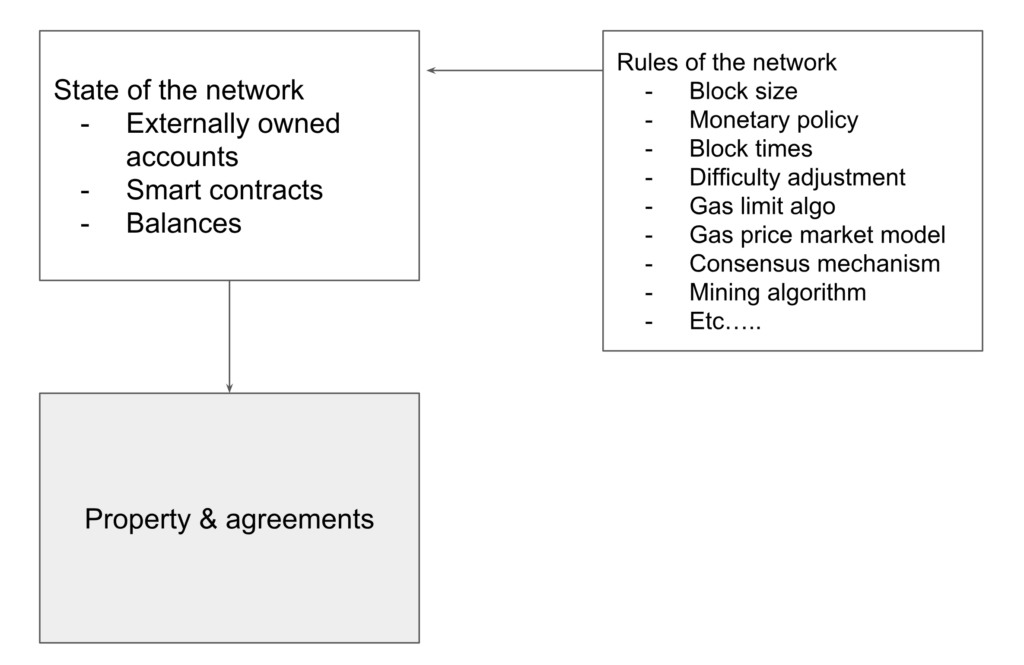

Implicitly, he distinguished the two parts that directly or indirectly affect the loss of integrity of blockchains: The state of the network and the rules of the network.

This is to say, the state of the network affects the integrity, or absence thereof, of money balances, property, and agreements directly, and the rules of the network (e.g. block size, monetary policy, choice of consensus mechanism, and others) affect the absence or presence of losses on a blockchain indirectly.

This is the model that emerges from the concepts above:

As the state of Ethereum Classic contains externally owned accounts (accounts controlled by people or machines) and their balances, and contract accounts (decentralized software programs) and their balances, I agree that this is the component that blockchains are looking to manage and protect with the highest level of security, by minimizing trusted third parties and preventing the tampering of the system using strong cryptography.

In other words, guaranteeing immutability.

Using the cause and effect chain of components in section 2 of this post, it can be said that rules or rule changes are hazards when they increase the risk of tampering with the state, which, in turn, creates losses in money, property, and agreements.

4. Dapps, Internet of Things, and Robotics

As described above, other kinds of losses may be the loss of actual functionality of systems that are built on top of ETC.

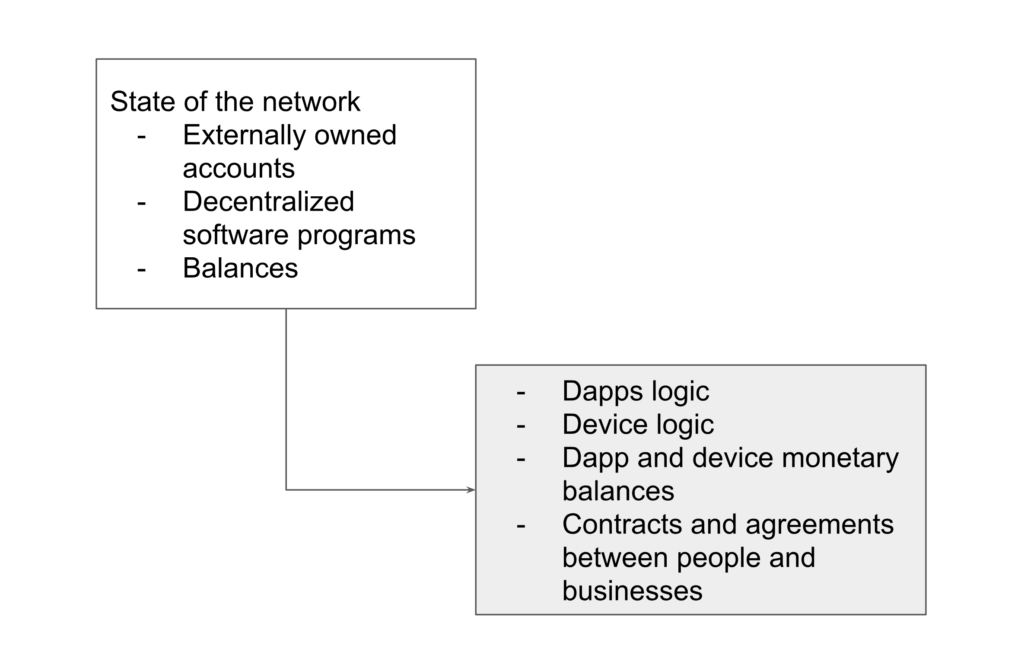

The positioning of the Ethereum Classic blockchain is that it will eventually power sidechains with more complex and high performance dapps, devices in the Internet of Things (IoT), and robotics such as self driving cars, rockets to space, or machines in manufacturing plants.

This means that the state of the network will include more things than just money, property, and agreements as described in the diagram below.

It is important to note that although the majority of people in the blockchain industry call decentralized software programs on the blockchain “smart contracts” the reality is that the networks really contain accounts, balances, and software programs, which when they are posted on the blockchain they become decentralized, hence “decentralized software programs” or “decentralized programs” for short.

Another important thing to note is that cash balances may be maintained on blockchains by people, businesses, smart contracts, and even by dapps or devices directly or through sidechains.

Conclusion

As many ask what is immutability, which parts of a blockchain are immutable, and which are not, or even question whether immutability in Ethereum Classic may hinder innovation in general, it is important to differentiate the components as described above.

The main goal of ETC is to protect the integrity of money, property, and agreements between people and businesses, and decentralized software programs and their balances, so that dapps and devices may operate safely on the blockchain in the long term.

This means that ETC’s state must always be immutable, and that the rules or some of the rules that support that immutability may change, but with utmost caution and always in the direction that increases security rather than trading it off for performance, scalability, or other policies that may really be hazards rather than improvements.

Code Is Law