The individual vs the collective fallacy says that individuals need to be selfless to benefit the collective, and that will create a better world.

However, the truth is exactly the opposite. The collective has to benefit the individual, and that will create a better world.

In fact, in this essay I will explain that the concepts of “collective”, “world”, or “group” are just mental constructs to facilitate some human behavior, but, ultimately, cooperative behavior exists because it is the most cost efficient way to benefit the individual.

Individual vs Group

In the last three million years, brain growth in the genus Homo has enabled humans to think in several orders of intentionality [1] (to be aware of oneself, and others at the same time up to a certain threshold, e.g. “I think that A thinks, that B thinks, that C thinks,…”…. and so on up to 4 to 9 orders), but also to anthropomorphize “groups” as entities with personhood in themselves.

This makes individuals think in multiple orders of intentionality for groups as well (e.g. “I think that my school thinks, that my community thinks, that my state thinks, that my country thinks, that the confederation of countries thinks”….and so on).

This anthropomorphism (very innate in humans as observed by animism [2]) also induces individuals to relate with groups as if they were other individuals.

This makes people conflate groups (e.g. the band, clan, tribe, city, nation, empire, or humanity) with other persons, thus creating the individualism vs collectivism false dichotomy (which is as difficult to explain as the concepts of money, time, being, meaning, soul, body, etc.).

The above is not exclusive to humans, as, perhaps with lower orders of intentionality, chimps, orcas, lions, meerkats, and many other social animals have very similar basic behaviors.

The above concept, that groups are mental constructs and that humans anthropomorphize them to relate to them as if they were other individuals, does not mean that actual groups of individuals don’t exist, or at least that it is not useful to relate to them as other cohesive entities.

The construct is useful in itself as it saves the mind time and energy in rationalizing reality, thus conducting behavior more efficiently.

For example, it would be very cumbersome for the brain to refer to one’s group of friends by the name of each individual and remembering each one’s specific preferences about things. It is less costly to create the entity of “my friends”, “the gang”, or “the guys”, and to sometimes relate to them as a unified entity with a unified average preference for things in general.

This creates the illusion that the individual components of the group, who may have different specific life plans and motivations, form a new overarching body with a single life plan and motivation.

Modeling Individual vs Group Dynamics

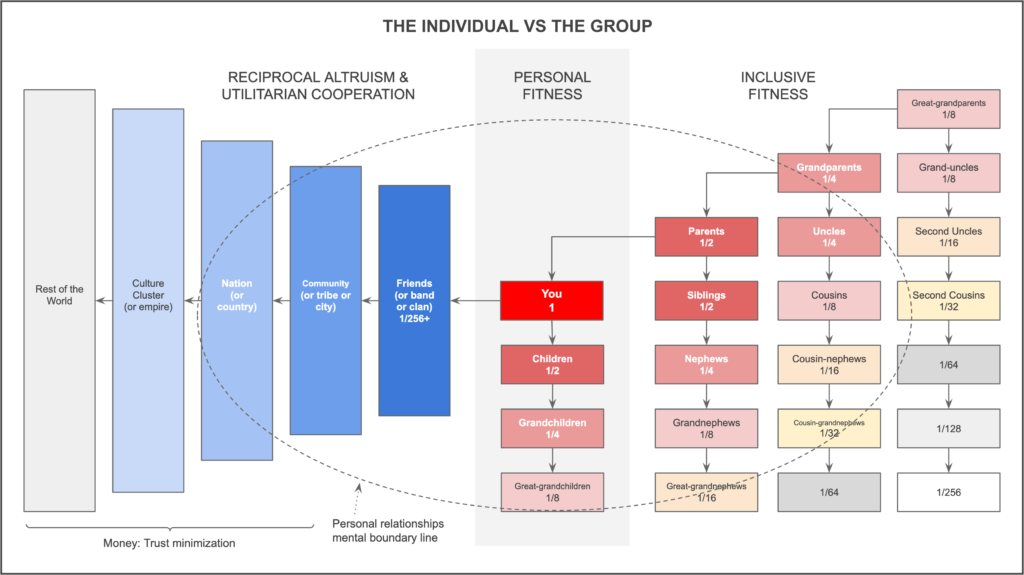

Below is a diagram of the general model for defining the individual and its relationship with groups.

Personal Fitness

Personal or individual fitness [3] in biology means the ability of the organism to reproduce or replicate its genes. The more healthy offspring that reaches adulthood to reproduce, the higher the fitness of the individual.

In diploid organisms as humans, direct descendants or offspring have a genetic relatedness of 1/2. The offspring of the offspring, or grandchildren, have a relatedness of 1/4, the grand-children 1/8, and so on.

The box “You 1” represents the individual. As explained by the Theory of Evolution, the individual seeks to replicate its genes.

The individual has a 1 to 1 copy of its own genes, but because it passes those to descendants combined with other individuals’ genes through sexual reproduction, it passes only 1/2 to them. This makes relatedness a marginally decreasing connection with offspring and other family members, or organisms of the same kin.

Also, if replicating their genes is the ultimate goal of organisms, and non-direct descendants share the same genes up to a certain extent, then producing direct descendants is not the only way of accomplishing the same goal.

Inclusive Fitness

The last concept above is called inclusive fitness [4], which means that the more healthy non-direct offspring that reaches adulthood to reproduce, the higher the inclusive fitness, because a portion of the organism’s genes will be replicated in the process.

In other words, as organisms are related to their parents in the same way as with their offspring, that means the parents’ other offspring, the siblings of the organism, are related as well.

For example, the siblings of an organism are related on average by 1/2 to it, and their offspring by 1/4; uncles are related by 1/4, and their offspring, the cousins, by 1/8; the second cousins are related by 1/32, and their offspring by 1/64;….and so on.

The theory of inclusive fitness means that organisms will actually invest time and energy in helping lateral or non-direct descendants to replicate their genes. However, because relatedness decreases marginally, the investment will also be decreasing proportionately.

The above means an individual will be interested in helping or cooperating with its nephews (1/4) less than with its own offspring (1/2), but will be willing to invest in them more than with cousin-nephews (1/16).

However, cooperating with unrelated strangers is an attribute of social animals as well, most commonly observed in humans.

Reciprocal Altruism and Utilitarian Cooperation

This cooperation with unrelated humans is seen in the diagram above on the lefts side of the individual, as it will typically have a group of friends with whom it interacts more closely and frequently, and each friend will typically reciprocate favors to it and other friends in the pack.

To follow the idea of genetic relatedness, friends could be considered outside of the genetic closeness of the family, but, because humans have common ancestors, however further away in time and space, friends are marked as related somewhere further than the 1/256 level (indicated as 1/256+), and the subsequent group layers are obviously further away and beyond.

The idea of the model is to show that there is a more direct genetic value in cooperating with groups on the right, and there is a more utilitarian value in cooperating with groups on the left with group constructs as “the guys”, “the team”, “the community”, “the nation”, the higher cultural clusters of nations, and eventually the rest of “the world” in general.

The key to understanding this natural drive to cooperate is that it is not to benefit the collective, or series of larger collectives in our minds, per se, but that the underlying evolutionary logic for that cooperation is to ultimately benefit the self [5], or, more specifically, the genotype of the individual, either directly or indirectly.

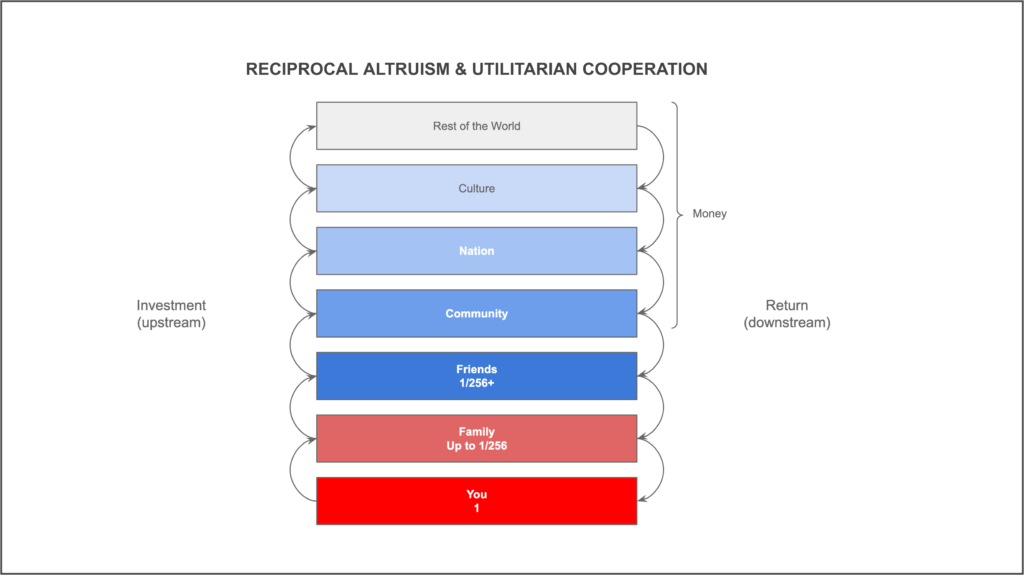

Below is the left side of the diagram where the collective levels are organized vertically to show how they are, or must be, functional to the individual.

The individual is part of a larger family. Outside of that genetic relatedness, it cooperates with friends in relationships that are more based on reciprocal altruism or delayed reciprocity [6]. It also participates in larger social or group constructs as are the community, nation, culture, and the rest of the world.

The investment that the individual makes to interact with all the layers goes in an upstream direction where the individual gives, reciprocates, or provides time and resources to the higher layer groups.

However, no social animal, individual, or mutant thereof, would exist today, or its genotype exist for very long, if there were no proximate or ultimate evolutionary payoffs to it, or returns on its investment.

This means that the investment made in “the collective” in its higher layers must eventually come back downstream as a genetic benefit, in the form of increased chances of replication, whether that payoff is in the form of direct descendants, or increased indirect descendants of the same kin.

The Personal Relationships Mental Boundary Line

An interesting observation about the “group” construct is the coincidence of Dunbar’s social relationship cognitive limit numbers of 5, 15, 50, 150, 500, and 1500 [7]; Hamilton’s rule, that genetic relatedness determines investment in altruism, therefore there are diminishing returns as marginal relatedness gets smaller [8]; Mancur Olson’s “small group” observation in Collective Action Theory, that small groups are more efficient than large groups because of the cost of coordination and free riding [9]; Social Group Theory in sociology, which acknowledges that small groups are more coordinated, recognizing the value of Dunbar’s observations [10]; and Social Ethology in animals, which describes alpha-beta group dynamics and hierarchy due to the scarcity of resources, coordination, and the perks and costs of status [11].

The scientists and disciplines mentioned above, from different perspectives, tend to arrive to similar conclusions about the physical and natural constraints of group size and social behavior.

The “personal relationships mental boundary line” in the first diagram above represents that general limitation of the mind to relate directly, with no intermediating devices, to other individuals.

This cognitive limitation is precisely why we have evolved to anthropomorphize groups as if they were persons, which results in a series of fallacies and flawed theories as the morality of the selfless individual, socialism, communism, the welfare sate, central planning, and juvenile and naive passions for “togetherness” and “save the world” activism.

Money as a Trust Minimization Device

The last part of the model is about the devices that humans have evolved to develop to overcome the mental costs and limitations of delayed reciprocity and the trust needed to interact with strangers. One of those devices is money.

In the last three million years, we have not only evolved to have larger brains to manage relationships with ever larger groups of individuals in our families, bands, clans, tribes, and beyond, but we have also developed a strong positive sentiment for things that are scarce, durable, costly to create, portable, divisible, fungible, and transferable [12].

The reason why this happened is that to be able to exchange one product for another in a trust minimized way, as, very frequently, they were not available at the same time by the same providers, there was a need for a third product to be valued by all parties so it could be exchanged in the meantime.

Money became that third product that all individuals and societies came to value and use to unlock cooperation and commerce between unrelated and untrusting parties.

Money eventually enabled civilization as we know it today.

Other devices developed by humans, very likely linked to our genetic evolution as well, are basic rights, such as property and agreements, religion, science, law, institutions, markets, and governance systems, amongst others.

Conclusion

In all cases, human individuals tend to anthropomorphize all these constructs mentioned in this essay and relate to them, in one way or the other, as if they were physical entities or other individuals, but they are not.

For example, we say “the science says” when it’s really the individual opinion of persons who happen to be scientists; or “the Supreme Court decided” when its really a few lawyers who individually gave their rulings about a legal subject; or “the market is up” when it’s really millions of independent buyers and sellers freely agreeing on specific prices for specific financial assets, commodities, or products; or “the government is corrupt” when in reality individual politicians, however ubiquitous, are corrupt.

Both individuals and groups exist physically, but the living entity with an information code in the form of heritable DNA, which directs and influences its cooperative behavior, is the individual.

Groups are only a useful mental construct, so the individual must never be diminished for an imaginary benefit to any collective [13]. Those are just mental tricks by other alpha individuals, who only want to take advantage of the naive, and a recipe for biological dysfunction [14].

References

[1] The Social Brain Hypothesis, by Robin I. M. Dunbar: http://etherplan.com/the-social-brain-hypothesis.pdf

[2] Animism, by Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Animism

[3] Fitness (biology), by Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fitness_(biology)

[4] The Genetical Evolution of Social Behavior II, by W. D. Hamilton: http://etherplan.com/the-genetical-evolution-of-social-behavior-ii.pdf

[5] The Logic of Animal Conflict, by J. Maynard Smith & G. R. Price: http://etherplan.com/the-logic-of-animal-conflict.pdf

[6] Reciprocal Altruism, by Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reciprocal_altruism

[7] Dunbar Numbers, by Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dunbar%27s_number

[8] Hamilton’s Rule, by Encyclopedia Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/science/Hamiltons-rule

[9] Mancur Olson’s Collective Action Theory, by Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collective_action_theory

[10] Social Group (sociology), by Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_group

[11] Alpha (ethology), by Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alpha_(ethology)

[12] Schelling Out: The Origins of Money, by Nick Szabo: https://nakamotoinstitute.org/shelling-out/

[13] The Fallacy of Collectivism, by Ludwig von Mises: https://mises.org/library/fallacy-collectivism

[14] Objective Versus Intersubjective Truth, by Nick Szabo: https://www.fon.hum.uva.nl/rob/Courses/InformationInSpeech/CDROM/Literature/LOTwinterschool2006/szabo.best.vwh.net/tradition.html

Code Is Law