You can listen to or watch this video here:

This article is a response to Vitalik Buterin’s comments about the “dishonesty” of projects with early on supply caps. Below I am posting his statements from the transcript on Reddit with my observations below each quote.

I think if people want a supply cap, then 140 million is a totally [achievable] number. Right now, the supply is 105 million, and when proof of stake launches, maybe the supply will be 110 million. Then at some point, we will be able to cut down the proof of work mining reward. Then at some point the proof of work chain will be retired entirely. Maybe at that point the supply will be somewhere in the high 110 millions to 120. Then when that happens, you could totally just follow the same formula I added in EIP 960 and have the issuance just taper off to 140. I think that is something that totally could be done. I think going toward 120 million as the number would be aggressive but 140 million could be achievable if people want a cap.

The supply cap choice in blockchains such as Bitcoin (BTC) and Ethereum Classic (ETC) does not primarily nor directly address the security proof of work mining provides. Mining can be paid with any currency, inflationary or deflationary, including fiat. This means that as long as miners receive revenues that cover their costs plus their expected return, they will invest in hash power, regardless of the medium used to pay them.

What the fixed monetary policies in BTC and ETC effectively and directly address is a property rights problem: With variable supply, as opposed to fixed supply, it becomes uncertain what share of the total stock any particular holder owns, moreover, variable supply policies almost always tend to eventually dilute individual ownership shares of money.

Because supply caps are a good way of solving the property rights problem in currencies, then those currencies tend to have increasing value. When currencies have increasing value, they can be used, amongst many other things, to pay for network hash power.

As a matter of coordination and as a token distribution choice, especially during the bootstrapping period, the currencies of proof of work blockchains are normally issued and paid to miners in the form of rewards in exchange for their work when producing very costly blocks. The fact that cryptocurrencies have demand for the security they provide, in the form of property rights, is the reason miners can actually use those rewards to pay for the resources they consume such as electricity and equipment.

It seems that in the quote above Vitalik generally agrees, “if people want”, with supply caps. As he expresses below, his objection is really that some projects do it “early on”. However, there doesn’t seem to be, to my knowledge, any logical explanation of why violating people’s rights “early on” is fine, but less fine “later on”, especially if supply caps are created precisely to secure property rights.

The other thing to keep in mind though is that one of the intuitive arguments I have against caps is that I feel like projects that institute caps early on, there is something dishonest to this decreasing reward schedule concept. And the reason why I feel it’s kind of dishonest is that you’re basically claiming two contradictory things at once. You’re using the present level of issuance of the system and the systems ability to operate under the present level of issuance as a proof that the system is safe. But then you’re using the fact that it has this baked in decreasing reward schedule as a proof that it’s finite supply. But then if it’s finite supply then the reward schedule is going to decrease and we have no evidence that the system is going to be safe under the decreased rewards.

As I wrote above, supply caps accomplish the goal of securing property rights, therefore they are totally consistent with their purpose, even more if that implies ending fixed rewards to miners at some point in the future, or through a decreasing reward schedule.

The above “block rewards vs insufficient transaction fees” argument is practically identical to Paul Sztorc’s argument that I refuted in a previous article. Paul argues that the “store of value” feature of Bitcoin, analogous to the “supply cap” objection by Vitalik, is currently paying for miner hashing power, but, as block space is supposedly unlimited through altcoins, and as current fees are very low compared to rewards, then fees will not compensate for the lost revenue miners will suffer. In the same manner, Vitalik is arguing that there is “no evidence” that fees will cover for the cost of hashing power in the future.

Paul and Vitalik are making two mistakes:

1. They are using the current depressed transaction volumes and fee levels as a proxy to demonstrate that fees alone will probably not cover mining costs in the future.

2. They are neglecting to acknowledge that in the future there will be very few chains at the base layer, therefore, highly secure block space will be very scarce.

Number 2 above means that future transaction fees will likely be much higher than today, therefore, together with higher volumes, will likely cover and probably even surpass today’s and future block reward levels to miners.

If we want a practical example of this it would be current Bitcoin fees today are about $140,000 a day and the current Bitcoin block reward is 12.5 BTC multiplied by 144 blocks which goes up to 1800 bitcoins a day which multiplied by $4,000 which is $7.2 million dollars a day. So Bitcoin going to a fees only model would decrease rewards by a factor of 50. But if you take Bitcoins mining power and divide it by a factor of 50, that’s not much stronger than what ETC has, and ETC got 51% attacked.

The example given by Vitalik above is a gross fallacy because not only is he wrongly using the current depressed fee levels as a proxy for future fees, but he is also falsely using ETC’s recent 51% attacks as an example of a catastrophic event, when what it really proved was exactly the opposite: that double-spends in proof of work blockchains are not a general network failure, but a local issue between sender and receiver, and that receivers can easily increase security of their incoming deposits by increasing confirmation times, as many important cryptocurrency exchanges have done.

It is also important to note here that proof of work in a blockchain achieves several goals other than just minimizing 51% attacks:

• It makes it extremely difficult to forge units of the currency, a key feature of functional money.

• Accumulated historic difficulty makes it practically impossible to reverse the chain after a given number of confirmations, even with 100% of network hash power.

• It establishes an objective cost for each currency unit which is then used as a proxy for its value in the economy.

The above illustrates that, although 51% attacks and double-spends have become the boogeyman everyone fears, that is only one of several benefits of proof of work.

So I think in general people should view promises of supply caps, even if they are backed by angry and ideologically excited people that are extremely attached to their [Schelling points]. I think people should view them as less credible than people generally view them now.

In this segment Vitalik does what he has been doing for a long time: To characterize Bitcoin maximalists, immutability and security buffs, and sound money and proof of work enthusiasts as irrational individuals who hold beliefs irrespective of their sound and thoughtful arguments.

The truth is that the one who has been bending reality, even when he knows it perfectly well, and going against any sound blockchain principle, is Vitalik himself.

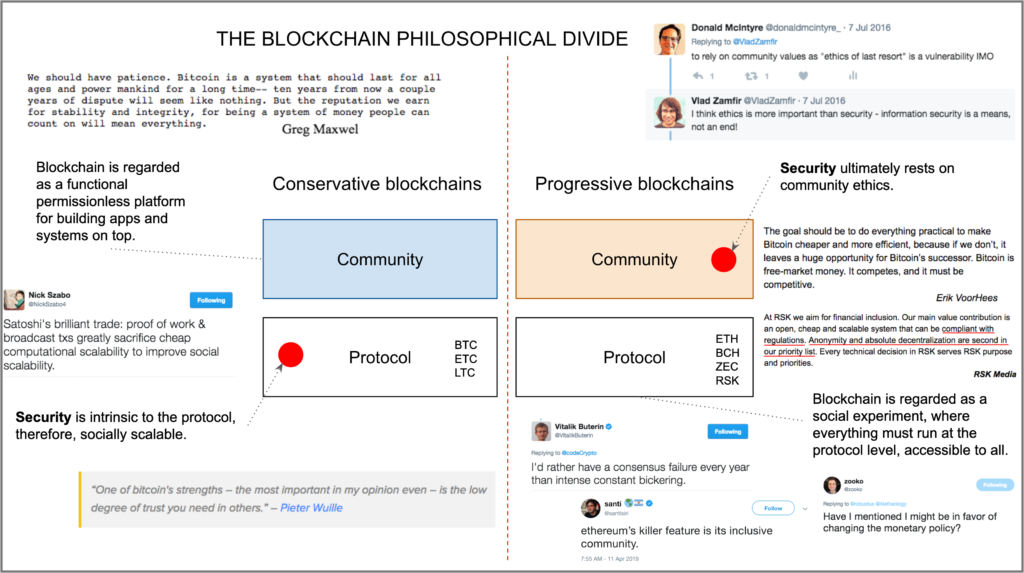

More proof of this is that he has consistently reneged on trust minimization as the main goal of public blockchains, has promoted unsound designs for Ethereum, such as proof of stake and sharding, has introduced subjective consensus at the social layer as a security assumption for what should be highly secure and objective systems, and, of course, has repeatedly argued against fixed monetary policy and in favor of changing supply whenever a small group of ‘intellectuals’, ‘cryptoeconomists’ and core developers decide to change it.

To the contrary, the people who Vitalik calls “angry and ideologically excited people that are extremely attached to their Schelling points” are actually the ones with the sound principles and promoters of best practices in public blockchains.

But at the same time there is this argument that Proof of Stake can achieve the same level of security much more cheaply than proof of work, and so maybe if proof of work with a supply cap can’t work, proof of stake with a supply cap can work.

Proof of stake blockchains cannot achieve the same level of security and sound game theoretical equilibrium as proof of work chains precisely because they do not incur in the same external costs that protect the several parts of the blockchain previously mentioned. Therefore, proof of stake fails against proof of work because:

• Its fault tolerance is 1/3 instead of 1/2, which even reduces its ability to minimize the feared 51% attacks.

• For the same reason, there is no barrier for staking nodes to get together to forge the currency.

• It has no historical accumulated difficulty, which means there is no barrier for staking nodes to get together to reverse the whole chain, all the way to genesis, with no cost whatsoever.

• No hash rate means there is no proxy for determining the currency unit’s value.

Conclusion

And if he wants to do the number on that, Ethereums current transaction fees per day are something like I think 500 Ether so if you take 500 Ether multiplied by 365 days a year, you get 180,000 Ether ever year. And 180,000 Ether every year basically means like the equivilent of 0.15% annual issuance. 0.15% annual issuance with 10% of the staking, that means 10% of the staking can get 1.5% annual reward. So it’s definitely not out of the question, but it’s an unproven hypothesis that 10% of Eth stakers will be willing to stake, in exchange for a 1.5% annual reward. So we’ll see. I think it’s almost counter-productive to argue about this too much before we have clearer numbers of how many proof of stake participants are willing to participate. Then after we have those numbers, things will get a lot more interesting.

In the above example, although referring to proof of stake, Vitalik is still making the mistake of using the current fee levels as a proxy for future fees when, in the future, it is very likely that block space supply will be very limited at the base layer, transaction volumes will be higher, and, therefore, fees will be much higher.

However, the relevance of Vitalik’s comments in this last segment is that the “we’ll see”attitude is an open door for arbitrary behavior that Ethereum developers have shown in the past e.g. TheDAO reversal, an irresponsible difficulty bomb to force the ecosystem to hard fork, the plans to move from proof of work to proof of stake with no scientific arguments whatsoever, to fragment the blockchains when maximal replication is one of the key, if not the most important security assumption in a blockchain, and, the main point of this article, frequently changing monetary policy.

Code Is Law